I admit that I’m late to the 3D printing game. While I just picked up my first printer in 2018, the rest of us have been oozing out beautiful prints for over a decade. And in that time we’ve seen many people reimagine the hardware for mischief besides just printing plastic. That decade of hacks got me thinking: what if the killer-app of 3D printing isn’t the printing? What if it’s programmable motion? With that, I wondered: what if we had a machine that just offered us motion capabilities? What if extending those motion capabilities was a first class feature? What if we had a machine that was meant to be hacked?

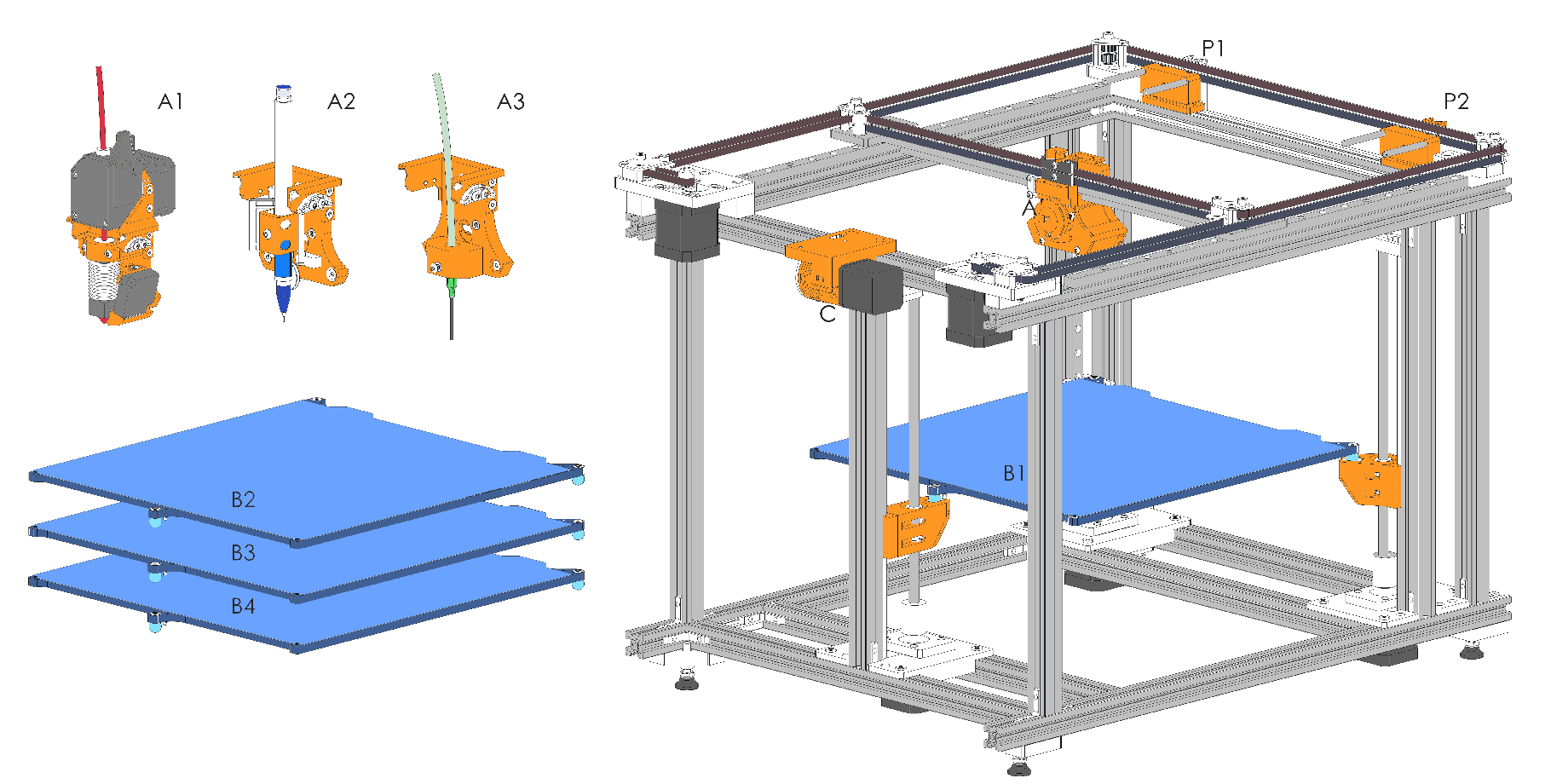

One year later, I am thrilled to release an open-source multitool motion platform I call Jubilee. For a world that’s hungry for toolchanging 3D printers, Jubilee might be the best toolchanging 3D printer you can build yourself–with nothing more than a set of hand tools and some patience. But it doesn’t stop there. With a standardized tool pattern established by E3D and a kinematically coupled hot-swappable bed, Jubilee is rigged to be extended by anyone looking to harness its programmable motion capabilities for some ad hoc automation.

Jubilee is my homage to you, the 3D printer hacker; but it’s meant to serve the open-source community at large. Around the world, scientists, artists, and hackers alike use the precision of automated machines for their own personal exploration and expression. But the tools we use now are either expensive or cumbersome–often coupled with a hefty learning curve but no up-front promise that they’ll meet our needs. To that end, Jubilee is meant to shortcut the knowledge needed to get things moving, literally. Jubilee wants to be an API for motion.

When it comes to precisely moving tools around in three-space, I’ve got you covered. As for defining what Jubilee can do, that’s up to you.

An API in Hardware

Playing with 3D printers can happen at all levels of the stack. Some folks build their own hardware from scratch. Others play with the software to generate a specific physical output. I’d loosely bin the hardware design as infrastructure as everything else as application. These days, creating a custom application often requires a bit of expertise in both domains. In designing Jubilee, I wanted to encapsulate the motion infrastructure into one platform so that others could readily build applications.

In object-oriented programming, there’s a design pattern called separation of concerns. The idea is that software should be written in modular form in such a way that one part doesn’t need to know the dirty details of another in order to invoke it. This principle is how software libraries are built. Libraries hide the complexity of the work that their doing and instead expose a clean application programming interface, or API, from which they can be invoked. Don’t get me wrong. The idea of modular hardware has existed for generations in engineering, but object-oriented programming does an excellent job of making these ideas explicit.

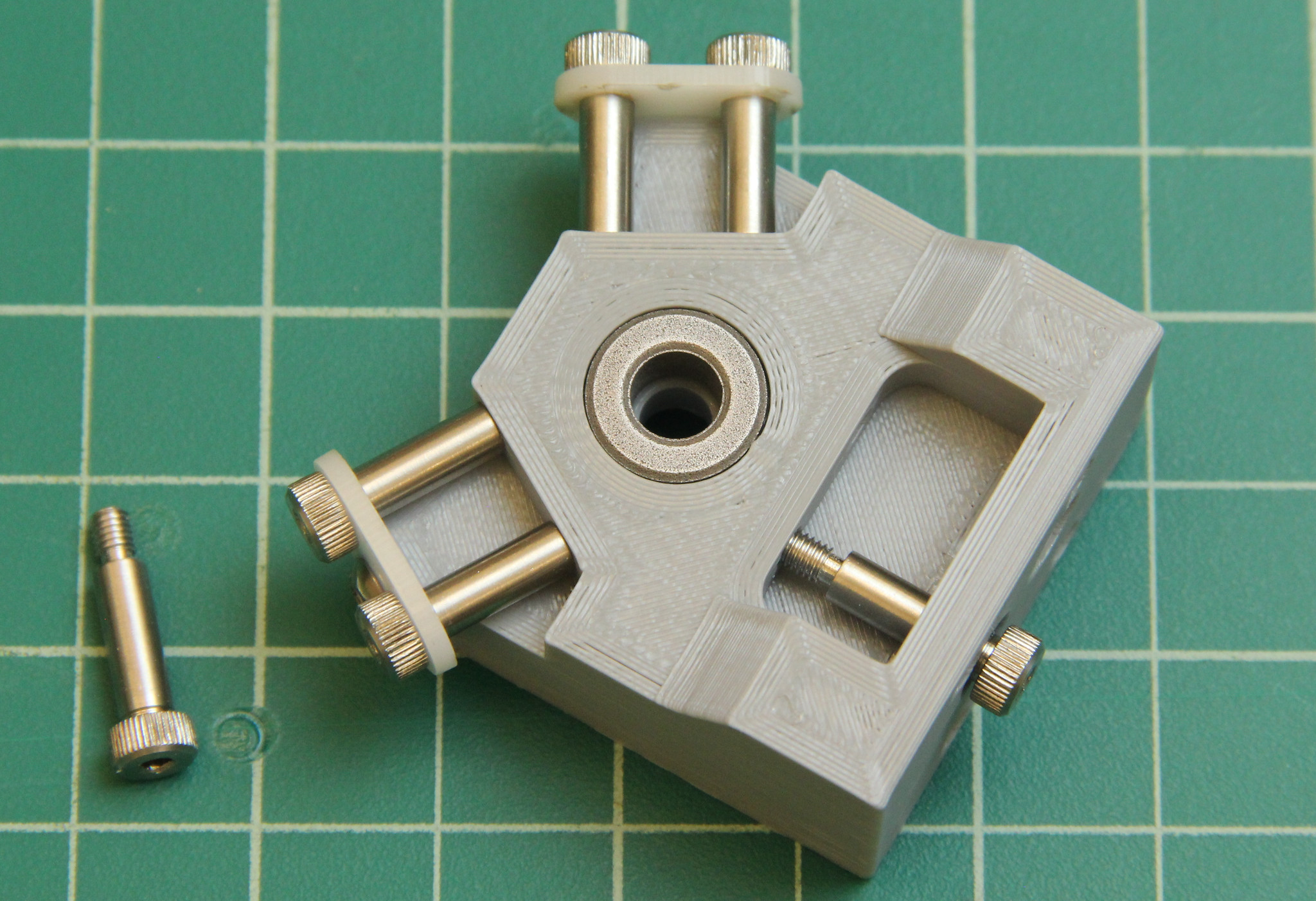

To apply separation of concerns to Jubilee, I needed to a way to decouple infrastructure from application. To do that I put kinematic couplings on both the machine carriage and the Z axis. Doing this makes both the bed platform and the tools removable. What’s more, since they are kinematically coupled, they can be removed and replaced over-and-over again without losing registration to the machine. The notion of an extremely repeatable system is what makes tool changing possible.

Toolchanging

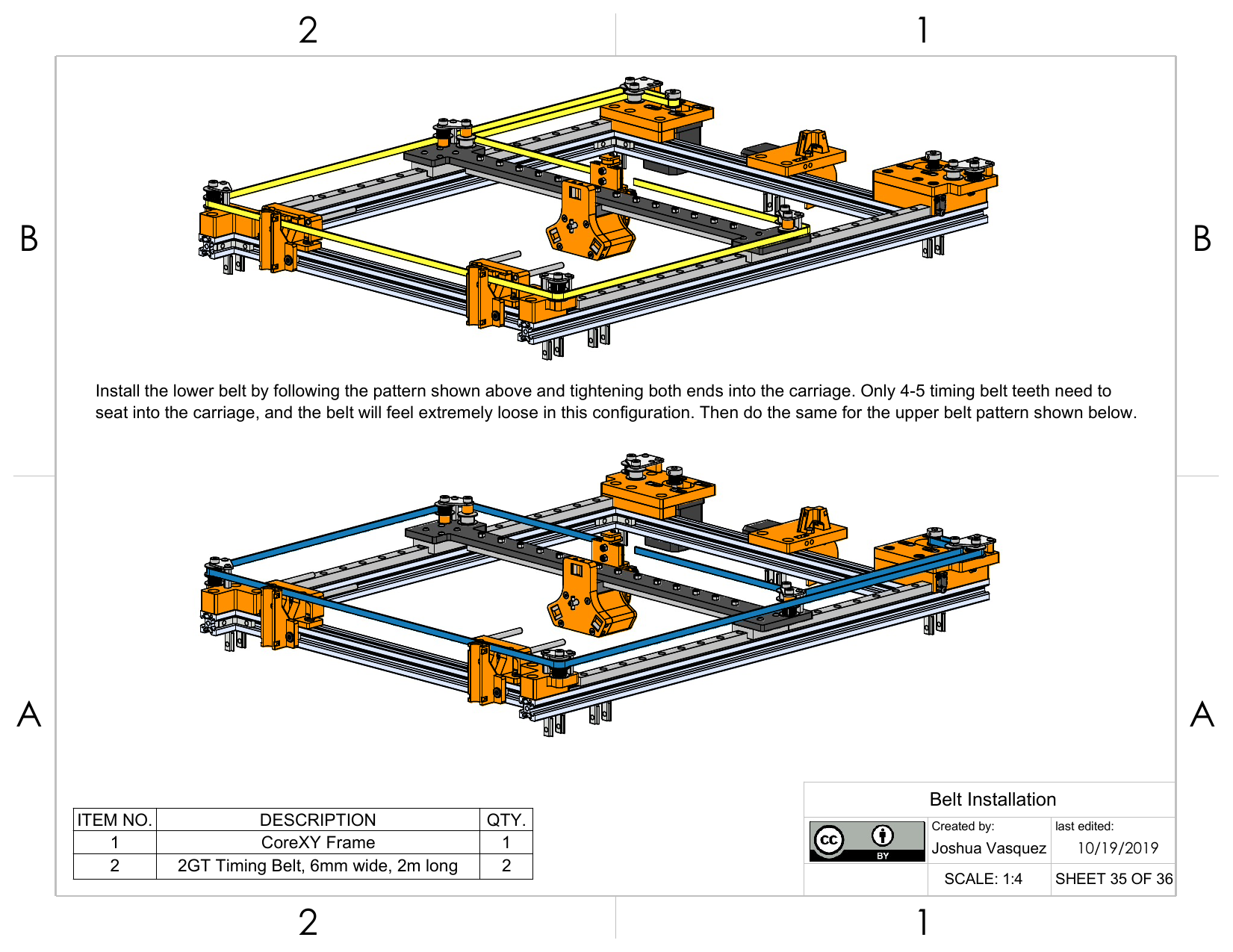

On Jubilee, tools are laid out in a rack on the front of the machine. When a task using one tool completes, Jubilee parks its current tool into the respective parking post and the picks up the tool for the next task automatically. All software logic for changing tools is handled by a script at the firmware level, making the slicer command as easy as invoking the number of the next tool you want to use, like T0, T1, etc. Like the separation of concerns pattern above, I did this to ensure that Jubilee’s hardware was as slicer-agnostic as possible.

My first toolchanging setup was inspired by this tweet from E3D back in 2018. In the months that followed, E3D kindly released the CAD files to their coupling system, and I modified the dimensions of my original design to be compatible with their tool plates. I’ll touch on how my setup differs in another post. But for now, what’s important to know is that the API is the same. In other words, an E3D plate and a printed Jubilee tool plate will both work.

Fabricatability

Here on Hackaday, we’ll catch ourselves describing hardware as “mostly-printed” and “self-replicating.” These words stem from the early days of RepRap, where the idea behind the RepRap 3D printer was that it could self-replicate. I personally love this narrative, but it has limits. Some machines, like lathes, have limited degrees of freedom, which limits the geometric features they can produce. Other machines, like 3D printers and laser cutters, can only produce parts from a limited range of materials. But what resonates so deeply with me is an underlying idea of bootstrapping our own personal fabrication capabilities from scratch. And through this narrative comes the notion of empowerment and self-reliance when individuals can transform raw materials into finished goods.

To take this narrative and turn it into something actionable, we needed a new word, a new design criteria. So our lab made one up. We call it fabricatability. Fabricatability is a qualitative word to describes a design’s ability to be fabricated by a single person without specialized tools and expert knowledge. Fabricatability is like manufacturability. But the difference is while manufacturability presupposes an understanding of the available manufacturing resources, fabricatability presupposes an understanding of the person, their access to tools, and their knowledge of how to use them. Similarly, design-for-fabricatability is like design for manufacturing where the manufacturer is one person with limited resources and minimal training.

The big idea is that, if we really understand the person, we can give anyone the capability to bootstrap their own infrastructure if we do a few extra things in our design that puts the person first. With Jubilee, I did my best to lay out the prerequisite knowledge up-front in the wiki. Jubilee’s off-the-shelf parts can all be purchased in low volumes without a pricey minimum-order quantity. Most of Jubilee’s fabricated parts use a 3D printer to avoid requiring skilled machine operation knowledge. Similarly, the design is intended for hand assembly by someone without expert hand crafting skills

Nothing’s perfect, though! While I tried to design Jubilee to eliminate machined parts, three parts must be machined. But to fill the gaps, some community machinists have kindly stepped up to make these parts for us in single quantities.

Instructions that hat-tip our brick-building heydays

I grew up with a healthy dose of LEGOs. At the time, I took for granted the instructions; they were just a means-to-a-spaceship. Looking back, though, I’m blown away by how cleanly they make the assembly process of a 500+ piece kit. Their style is both succinct and explicit. All required parts are called out up-front per page. Heck, if you’re building with a friend or loved one, you can even parallelize the process where one person does the brick-laying while the other scoops out parts for the next step. (Anyone else have a fond LEGO date night in their past?) The style translates to many languages–because there are no words! Heck, I’m pretty sure I could read LEGO manuals before I could read books! And it’s consistent. Once you’ve built your first set, you’ve got a pretty clear idea of how the format of the instructions go for the next one.

Jubilee’s instructions are inspired by my brick-building heydays. First off, in the design, parts need to have fully-constrained attachment points as much as possible. What that means is that parts need to seat together in only one way. They can’t slide back-and-forth in a range of movements, or different people will assembly Jubilee in different ways, some of which wont work! That’s where the instructions come in. Steps are called out visually in step-by-step fashion to minimize words. Tuning instructions that use special tools are also detailed visually. My hope is that anyone, not just a seasoned machine builder, can build Jubilee following the assembly process in the docs. Finally, to help folks along the way, I made a Discord channel for folks to ask assembly questions and joing the community discussion at large. Feedback on Discord is also most welcome! I’m doing my best to channel it into improvements in the instructions and wiki docs.

Pushing the Limits

While a one-machine-fits-all CNC-machine-for-everything sounds cool, it’s not Jubilee. Rather, Jubilee is intended for non-loadbearing applications only. These days, I’ve put the most effort into transforming Jubilee into a rock-solid multitool printer–but even then I’m still twiddling print settings to find a middle-ground that I like.

So even though Jubilee can’t juggle heavy cutting tools, it turns out that the space of what Jubilee can do is still quite rich. Apart from 3D printing, my labmates and I have played with multitool liquid handling with syringes, mulitcolor pen plotting, an image-stitching with a USB microscope.

Finally, I have too many things to say in one post, but I promise I’ll cover some of my favorite hardware details soon.

Research Findings for All

A year ago, I packed up my garage machine shop and took the leap into grad school. For me, a PhD has been the final major roadblock to becoming a teacher. Like it or not, I would need to face it. Bur rather than make grad school a 5-year holding pattern for a future in teaching, I wanted to find some way to make the experience meaningful others, not just myself, now, not after I graduated. One year into this misadventure, I am thrilled to say that Jubilee is both for and inspired by you, fellow hackers. It’s a piece of me out there in the world that I hope is meaningul to you. It’s not perfect, but it’s functional, something we can all build on.

When I started this project nearly a year ago, I’d occasionally post a progress video to document the good-and-bad. It’s crazy to think that a year ago we went from this:

to this:

Admittedly, as far as grad school labs go, I lucked out. I met a professor, Nadya Peek (at a Supercon!), who helped establish the first FabLabs in the early days of the open source hardware movement. It’s through her efforts that my hands are free to tackle projects like Jubilee. And it’s through her shrewd negotiating that our lab is able to release all of our designs as open source for you, fellow hacker–no strings attached!

And with an open design, we can start riffing off of each other’s ideas and expanding the toolchanging ecosystem for everyone. In the last month, a few folk have already kicked off their own Jubilee build. Some are already changing tools!

But why let us have all the fun? Jubilee’s docs, BOM, and CAD files are in the wild for you to enjoy. Now has never been a better time to jump into a world of ad hoc automation. So go forth and create your own personal adventure into toolchanging. Share your whoops and woes on the Discord. And, of course, write to us on Hackaday if you get Jubilee to do something awesome.

(Finally, if you think grad school is cool, why not come hang out with us?)