Last year marked the 30th anniversary of the Internet Relay Chat protocol (IRC) and it is hard to imagine that [Jarkko Oikarinen] could have foreseen the impact his invention would one day have on the world as we know it. How it would turn from a simple, decentralized real-time communication system for university-internal use into a global phenomenon, connecting millions of users all over the world, forming its own subculture, eventually reaching mainstream status in some parts of the world — including a Eurodance song about a bot topping European music charts.

Those days of glory, however, have long been gone, and with it the version of an internet where IRC was the ideal choice. What was once a refuge to escape the real world has since become the fundamental centerpiece of that same real world, and our ways of communicating with each other has moved on with it. Nevertheless, despite a shift in mainstream and everyday communication behavior, IRC is still relevant enough today, and going especially strong in the open source community, with freenode, as one of the oldest networks, being the most frequently used one, along some smaller ones like OFTC and Mozilla’s own dedicated network. But that is about to change.

Last month, Mozilla’s envoy [Mike Hoye] announced the decommissioning of irc.mozilla.org within “the next small number of months“, and moving all communication to a new, or at least different system. And while this only affects Mozilla’s own, standalone IRC network and projects, and not the entire open source community, it is a rather substantial move, considering Mozilla’s overall reach and impact on the internet itself — past, present, and now even more the future. Let’s face it, IRC has been dying for years, but there is also no genuine alternative available yet that could truly replace it. With Mozilla as driving force, there is an actual chance that they will come up with a worthy replacement that transforms IRC’s spirit into the modern era.

Well, the good news is, we won’t have to bury IRC just yet, and most likely never will, but this still seems like a good moment to pay our respects to a protocol that turned into a lifestyle, and ponder on its future.

A Walk Down Memory Lane

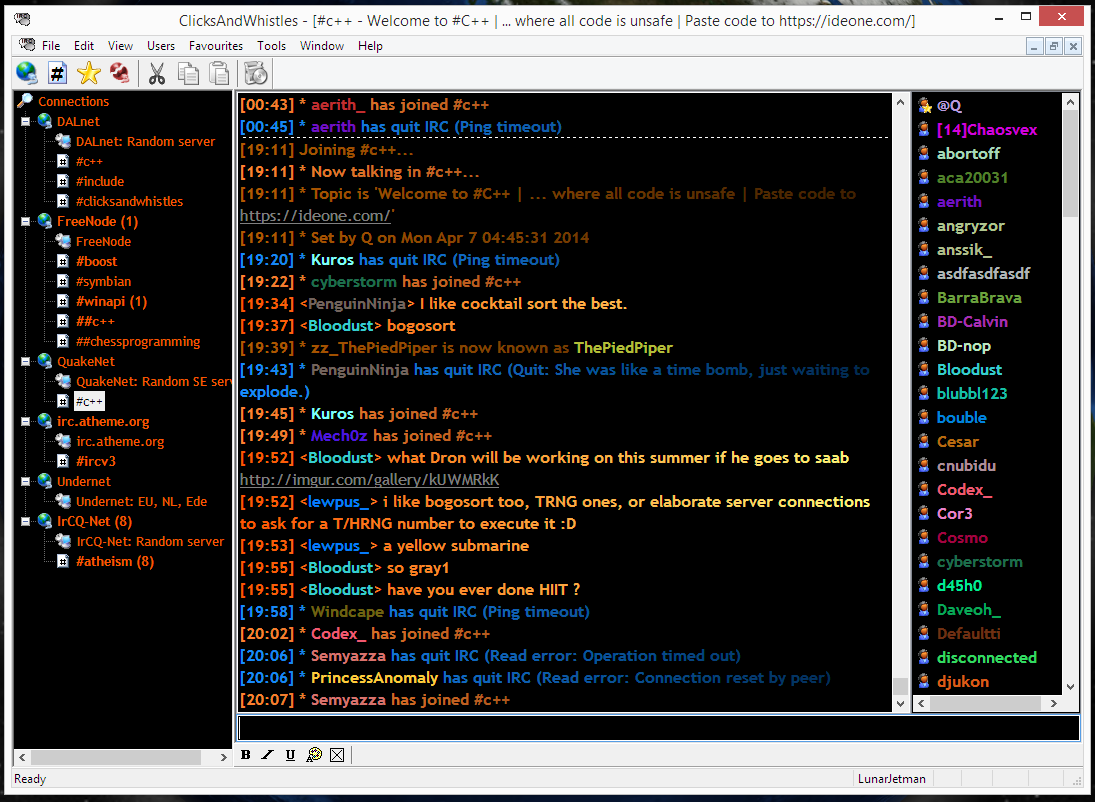

Although I was too young to read or write at the time it was created, and didn’t encounter it until later in my teenage years, IRC has been a major part of my life, and it most certainly defined who I am today. Once it entered my life, IRC took me far beyond the countryside village I was growing up in, and opened up a whole new world for me. It was in fact mIRC’s built-in scripting language that sparked my very first interest in programming, bots and bouncers that made me enter the realms of Linux, and the Wild West times of internet warfare that got me curious about networking and security. By the time IRC reached its peak in the early 2000’s, my entire social life had practically ceased to exist outside of it, and although other factors played a role in it as well, it is not a coincidence that I eventually ended up living in the very same city where IRC was born.

IRC’s Influence On Technology

While those are of course just personal, anecdotal experiences, there’s a far bigger picture to it, and IRC has played an important role in the development of the internet itself. Take IPv6 for example: we’ve heard for decades how the IPv4 address space is soon going to be exhausted, and IPv6 has been around as the promising savior for the majority of that time already. Yet it’s only become relevant to the wider public in the last few years, with ISPs slowly adapting to offer native IPv6 connections. Meanwhile, IRC servers supported IPv6 at the end of the 90’s, providing an actual real-world application for the new protocol, and an incentive for projects like XS26 and SixXS that offered IPv6 access to the general public by tunneling it over IPv4.

For anyone interested in anything related to networks or server administration, this was a wonderfully exciting new playground, and with the incomprehensible vast amount of addresses available within the IPv6 space, you could keep yourself busy for days just thinking of ways to put in perspective the number of IP addresses you had at your own, personal disposal now. But while you could have used a unique IP for each and every website request you ever make, it was in the end IRC that provided the best experimental environment for it, especially as it meant a virtually unlimited amount of possible IRC connections. This made it a lot easier to run several clients at once, even offering it as a service to others, and of course increase the presence of botnets, both for good and for evil.

After all, IRC has always been the early internet battle field. Its general structure with interconnected servers, and channels with different privilege levels and authorities easily attracted rivalry and caused power struggles. Taking over channels became a favorite pastime for some people, and entire IRC crews have formed with the sole intention to terrorize and seize power over channels. These were the untamed times of attacking individual network connections to remove the channel operators or protective bots, large-scale DDoS attacks against IRC servers to cause netsplits and gain operator status on an isolated server, compromising other machines to run additional clients or bots for stronger numbers, or to circumvent geographical limitations of servers in other parts of the world. While those attacks weren’t necessarily new, IRC warfare gave somewhat of a wider and seemingly less consequential purpose for them, even if it was just for virtual dominance and the ego. They became common enough to raise awareness of weaknesses and vulnerabilities in networks and operating systems these attacks were exploiting, which over time improved their overall security.

IRC’s Influence On Society

But the technical aspects aside, IRC has always been social. Of course, communicating with strangers on the internet wasn’t new, UseNet and BBSes had been around for years, but connecting people all over the world with each other in real time offered whole new possibilities. Chances are you would find channels dedicated to your city or area, to your hobbies and other interests, and all kinds of general chitter-chatter. You could get in contact with strangers you probably never would have met otherwise, sharing the same interests and discussions, free from most bias and prejudice. You could get in touch with opinions and life circumstances outside your own bubble, and you could get to know a person without ever seeing them. The world felt never bigger yet so intimate at the same time.

IRC formed a life of its own that overlapped with the real world, and sparked new ventures in the online world. Channels formed ecosystems of their own, a unity to identify with. They had their own websites and held semi-regular user meetings where everyone would gather in a pub or a field outside town. Offline relationships started in IRC. The anonymous strangers who you only referred to by their nick suddenly became real persons. Predecessors of social media platforms emerged to follow-up your IRC presence, with Finland’s irc-galleria still alive and kicking to this date.

IRC formed a life of its own that overlapped with the real world, and sparked new ventures in the online world. Channels formed ecosystems of their own, a unity to identify with. They had their own websites and held semi-regular user meetings where everyone would gather in a pub or a field outside town. Offline relationships started in IRC. The anonymous strangers who you only referred to by their nick suddenly became real persons. Predecessors of social media platforms emerged to follow-up your IRC presence, with Finland’s irc-galleria still alive and kicking to this date.

Altogether, it was a wild and oftentimes surreal experience — no doubt nostalgia plays its role here, too. But the internet has simply changed since. IRC servers were predominantly run by volunteers in universities, research institutes, ISPs, and some smaller, pioneering tech companies. It was a free and open space, a place for exploration, with all the pros and cons that comes along with that. It was a landscape of thousands of individual channels, all doing their own thing, having their own rules and customs, and their own set of people in charge to keep things in control. IRC operators kept an eye on the servers and the network itself, but generally didn’t bother much about channel-internal business if they weren’t actively a part of it, as long as everything else was peaceful. It was everyone for themselves, but still together. Sadly, that doesn’t fit too well in today’s surroundings anymore.

The Future Of IRC

So, is Mozilla’s decisions to abandon IRC going to have a larger impact on the remaining networks? Probably not. IRC’s decline isn’t a recent development, and since irc.mozilla.org is a standalone system for development inside Mozilla itself, in the big picture, it’s really more their personal problem. But as mentioned in the beginning, with the right angle, they might contribute a worthy replacement — and that could be a whole different story for IRC itself then.

Admittedly, IRC does feel archaic today, and clearly stems from a time where data didn’t just magically appear from a cloud and communication details weren’t abstracted away. And it didn’t have to, it was basically a given to familiarize oneself with enough knowledge up front to be able to navigate about, which also helped filtering out the normies from the real world pestering one’s sanctuary. That gatekeeping attitude doesn’t work anymore though. Once again, the internet has changed; the audience, the content, the majority parties running the show behind the curtain, and the way people communicate with each other online have just changed since “back in the day”. Simple text just won’t do it anymore, people need emojis and memes to express themselves nowadays.

While some aspects of this change are of questionable value, others should be appreciated and considered as an achievement. With all the fond memories I have about the golden days of IRC, I very much enjoy the progress we have made since, and the fact how normal and everyday the internet in general has become. Still, none of the modern forms of communication can replace what IRC was, and still is.

Sure, the concept of channels also exists in most modern systems, but the large-scale interconnectivity and openness of IRC doesn’t. It’s everyone for themselves more than ever, with commercial entities competing for users in their own, isolated environments. And it makes perfect sense from a professional point of view — you wouldn’t really want to have company-internal communication in a public IRC network. Setting up a private network is of course an option, but if you go that far, you might as well choose Slack or the likes, with all its conveniences and modern feel. But from an open source point of view, it doesn’t sound like a desirable future where every project has its own communication channels in place, separated from all other projects. Any sense of being a community in the bigger picture would simply be lost this way.

Well, we will see what Mozilla’s next steps are. The good news is that even if they make the “wrong” decision, it’s unlikely that it will have any lasting effects on IRC itself. But it would be a greatly missed opportunity to create an updated version of IRC that would fit in today’s world.