As the prospects for Germany during the Second World War began to look increasingly grim, the Nazi war machine largely pinned their hopes on a number of high-tech “superweapons” they had in development. Ranging from upgraded versions of their already devastatingly effective U-Boats to tanks large enough to rival small ships, the projects ran the gamut from practical to fanciful. After the fall of Berlin there was a mad scramble by the Allied forces to get into what was left of Germany’s secretive development facilities, with each country hoping to recover as much of this revolutionary technology for themselves as possible.

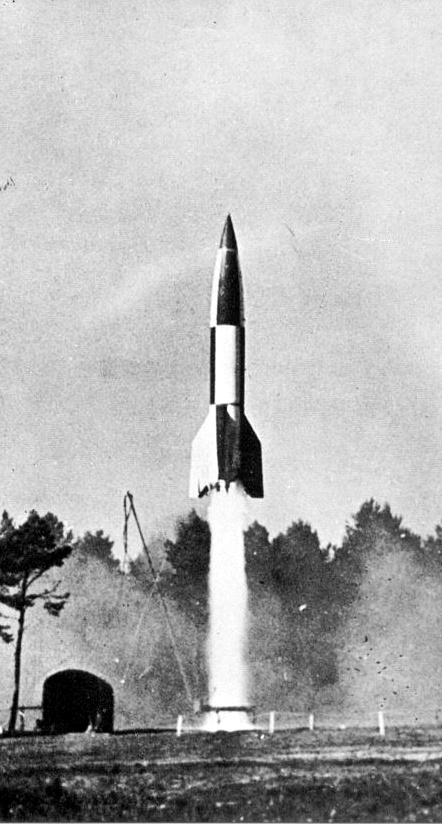

One of the most coveted prizes was the Aggregat 4 (A4) rocket. Better known to the Allies as the V-2, it was the world’s first liquid fueled guided ballistic missile and the first man-made object to reach space. Most of this technology, and a large number of the engineers who designed it, ended up in the hands of the United States as part of Operation Paperclip. This influx of practical rocketry experience helped kicked start the US space program, and its influence could be seen all the way up to the Apollo program. The Soviet Union also captured V-2 hardware and production facilities, which subsequently influenced the design of their early rocket designs as well. In many ways, the V-2 rocket was the spark that started the Space Race between the two countries.

With the United States and Soviet Union taking the majority of V-2 hardware and personnel, little was left for the British. Accordingly their program, known as Operation Backfire, ended up being much smaller in scope. Rather than trying to bring V-2 hardware back to Britain, they decided to learn as much as they could about it in Germany from the men who used it in combat. This study of the rocket and the soldiers who operated it remains the most detailed account of how the weapon functioned, and provides a fascinating look at the incredible effort Germany was willing to expend for just one of their “superweapons”.

In addition to a five volume written report on the V-2 rocket, the British Army Kinematograph Service produced “The German A.4 Rocket”, a 40 minute film which shows how a V-2 was assembled, transported, and ultimately launched. Though they are operating under the direction of the British government, the German soldiers appear in the film wearing their own uniforms, which gives the documentary a surreal feeling. It could easily be mistaken for actual wartime footage, but these rockets weren’t aimed at London. They were being fired to serve as a historical record of the birth of modern rocketry.

A Product of its Environment

While the V-2 is perhaps second only to the atomic bomb as the most complex piece of hardware produced during the Second World War, it’s interesting to see just how low-tech certain elements of the rocket really were. To modern eyes, the construction and handling of these deadly rockets seems amateurish to the point of being nearly comical. Some of that is due to the limitations of the era, as the V-2 was pushing contemporary technology to the absolute limits. But it’s also important to remember that V-2 was designed as a weapon of war, to be operated on the front lines by soldiers who up until this point probably didn’t have first-hand experience with anything more complex than a tractor. The V-2 wasn’t treated with the respect one affords an instrument of scientific endeavor simply because it wasn’t one.

The rockets gets jockeyed around with whatever means were available, such as the general purpose portable crane and ropes used to unload them from rail cars when they arrive at the launch site. Often men grab hold of the rocket’s fins and simply yank the vehicle into position. When disconnecting the frozen liquid oxygen lines from the rocket, they are beaten with hammers to loosen them up. All the while, several of the German soldiers can be seen with cigarettes dangling from their mouths. These men weren’t rocket scientists in the literal or figurative sense of the term, and yet they managed to send over 3,000 V-2’s towards their targets in a span of less than seven months.

But the way these rockets were handled during the war isn’t the only surprise documented by Operation Backfire. Seen up close and personal as it is in this film, the rough-hewn nature of the V-2 itself is readily apparent. The skin of the rocket is dimpled and wrinkled, panels are ill-fitted to each other, and under the stress of movement and fueling some of the joints open up enough that a worker needs to climb a ladder and tighten them before the rocket is launched. Built with great haste and often by slave laborers in abysmal conditions, the failure rate for the V-2 was exceptionally high. According to research conducted during Operation Backfire, the Germans learned to launch each V-2 within 72 hours of its assembly; any longer than that and it became increasingly unlikely to function.

Glimpses of the Future

While the V-2 and the men who operated them may lack the sophistication we associate with modern rocketry, one can’t help but notice similarities between these grainy black and while recordings of early launches and the ones we watch live streamed on the Internet today. Details which may now seem obvious were then yet to be fully understood, and every V-2 that managed to crawl its way into the air was another lesson learned. While the men in the film likely didn’t realize it at the time, they were discovering the protocols and best practices that are still in use over 70 years later.

For example, the film takes the time to explain why the rocket can’t be loaded with propellant until it has been erected vertically on the launch pad. Just as with modern rockets, the internal tanks of the V-2 could only support the massive weight of the propellants when they were standing upright. To an audience in 1946 this would likely have seemed a very strange way to design a vehicle, but but today we understand it as standard element of rocket design.

Similarly, the film explains that the German teams who fired the V-2 found that they had the best results when loading the frigid liquid oxygen (LOX) into the rocket as close to the launch as possible. Ideally, within one hour of liftoff. Any later and not only could too much of the liquid oxygen be lost to boil off, but the valves inside the rocket had a tendency to freeze solid. Yet as recently as 2016, SpaceX was still struggling to find the proper time to load supercooled liquid oxygen into their Falcon 9 booster; with a series of launch aborts due to liquid oxygen being loaded too soon.

A Painful Record

Even to modern eyes, there’s something almost perverse about The German A.4 Rocket. Seeing Wehrmacht soldiers preparing a V-2 rocket as if it was about to be sent screaming towards London at Mach 4 is bit like watching captured Islamic State fighters demonstrate the construction of a roadside improvised explosive device. It’s hard to imagine how someone watching this film in 1946 would have felt about what they were seeing, especially those who lived in London or Antwerp during the V-2’s operational use. To be sure, the circumstances surrounding the creation of this film are nothing less than extraordinary.

But the alternative, allowing this knowledge to become lost to time, was a far more unsavory prospect. When Operation Backfire was completed, the British government had no way of knowing if the information they had collected would be used for the betterment of mankind or not. They only knew that the V-2 program came at an incredible cost, not only in material but in human lives, and that allowing it to be forgotten would have been an injustice. A sentiment that is perhaps best expressed by the final line of dialog spoken by the narrator, as a V-2 roars into the sky:

We cannot afford to be complacent about the rocket and its potentialities in the future. The record of this film is a warning that we’ve got a lot to think about.

[Thanks to BrightBlueJim for the tip.]